UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES

My parents, Aura Allende and Julio Celis, separated early, but they maintained a good relationship. My mother worked in statistics at the National Medical Service. My father was a sculptor of religious figures and worked mostly in the catholic church. This is why I was educated at the Institute Alonso de Ercilla in Santiago, Chile. It was not just a school but a spiritually rich environment where students learned from Monday until noon on Saturday, went to Sunday mass, and took home a weekly notebook. Though challenging, the rigor and discipline of this institution instilled in me a deep sense of perseverance and teamwork that I carry with me to this day.

I got used to doing something related to studying every day, and I always kept myself prepared. I never appreciated it, but now I reflect that for many years, I have done this every day from 8 a.m. until late at night. Being successful depends, in one way or another, on consistency, perseverance, and discipline.

Without a doubt, what I have always liked the most is biology. It is not an exact science, like mathematics or physics, where one can predict. Biology is more complex; it is more than one plus one and two; you must work on the system to understand it. When you grow up, you realise how important it is to have a teacher who can take you beyond what you should know; through their example, it has much more value than reading and memorising a text. Now that I remember, at school there were small rooms with animals or human remains preserved in formalin; that may be why biology caught my attention. Sometimes, the teacher would bring an animal to show the dissection of some organs so that we could understand how they functioned in the organism; that interested me.

GRADUATE STUDIES: CHOOSING MY CAREER

One day, I stumbled upon a unique opportunity in my quest for a biology-related degree. While the conventional path might have led me to medicine, the allure of research was irresistible. It offered a taste of independence that I found lacking in other fields, a unique flavor I could not resist.

Living on Seminario Street, near Providencia in Santiago, I strolled past the School of Pharmacy on Vicuña Mackenna one afternoon. A light-brown wrapping paper sign with some letters painted with a marker caught my eye. It read: New Biochemistry degree, training future researchers. Twenty-five places, so I said to myself, “Well, maybe this is my career.” I applied and was accepted. It was a serendipitous moment that filled me with excitement and anticipation.

The career program was impressive. During the first three years, we had basic courses such as mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, botany, and several others shared with pharmacy students. In the last two years, we had pharmacology, biochemistry, clinical biochemistry, physiology, microbiology, and others. This setting was key as biochemists were increasingly needed to address clinical issues. The program creator, Osvaldo Cori, was pivotal in fostering a solid, basic education that encouraged flexibility and openness, helping individuals choose their career paths. After five years of study, you have completed the Biochemistry license.

Today, such an education is essential, and the career program’s adaptability is a key factor in its continued relevance.

CURRICULAR EXPERIENCE

My curricular experience at the University of Chile was unique, not following the typical paths in the USA or Europe. At conferences, I was often mistaken for a doctor. There were too many branches, but I realised the value of multidisciplinary training. It equips you to adapt to the changing scientific landscape, allowing you to choose your path without losing context. I initially delved into basic science, but the evolving nature of science led me towards medical applications, a journey that enlightened me about the value of multidisciplinary training in the scientific field.

MY CLASSMATES

Our class was filled with great classmates and phenomenal promotions. Among the 18 of us, several achieved remarkable success, including Cecilia Hidalgo and Pablo Valenzuela, both recipients of the Chilean National Science Award. Their achievements are a testament to the potential and talent of our class. The course was a tight-knit group, and we still maintain ties, often meeting at various conferences worldwide. But it wasn’t all about academics; we also had a blast playing competitive University basketball with our friends from Pharmacy under the leadership of Costanzo Bernardi.

After completing five years of studies in Biochemistry, I finished the license, and the next step was to undertake a thesis to graduate as a biochemist, the equivalent of a master’s degree today. The challenge was finding a top scientist to work with. Some of my classmates chose to write their theses under the supervision of Osvaldo Cori, a prominent figure in our field. Then, while reading the newspaper, I learned that the renowned Chilean scientist Jorge Allende (Fig. 1) was returning from the United States with his wife, Catherine Conelly, after completing postdoctoral studies with the Nobel laureate Fritz Lipman at Rockefeller University. Jorge had established a laboratory in the Department of Biochemistry at the Medical School at the University of Chile, and I asked him if I could do my thesis on aminoacyl tRNA synthetases with him. To my Joy, he agreed.

I was one of the first biochemistry students of my promotion to leave the Faculty of Pharmacy to do my thesis at the Department of Biochemistry of the Faculty of Medicine.

Even before Jorge Allende arrived, Hermann Niemeyer had a very active group that contributed significantly to the Department of Biochemistry, which was under the direction of Julio Cabello, a prominent figure. The Department had a strong tradition and a solid pedigree, with the unmistakable influence of Allende and Niemeyer.

There, I met Ariana Pfeiffer (Fig.2), who later became my wife and the cornerstone of my scientific journey. She was a technical assistant to Niemeyer, one of the most fascinating individuals I met. He was instrumental in shaping our shared path.

After I wrapped up my thesis, Jorge proposed that I consider a doctorate in the USA. He introduced me to Thomas Conway (Fig.3), a scientist with a prestigious history of working with Nobel laureate Fritz Lipmann, who was not just willing but eager to guide me. With my English skills still developing, Jorge and his wife took it upon themselves to assist me in the visa application process at the consulate.

PhD IN IOWA CITY (USA)

Iowa was a serene and tranquil place, a small rural state dotted with endless corn plantations. Our home was among these peaceful cornfields.

In the beginning, adapting was challenging as I needed to learn the language. Learning a new language with its unique grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation was daunting. I often struggled to express my thoughts and understand the lectures, but with perseverance and practice, I gradually improved. This journey is a testament to the power of persistence and practice in overcoming challenges, and I hope it instils hope in those facing similar obstacles.

My thesis was about the T2-dependent synthesis of bacteriophage-related proteins. The thesis, which I continued later in Chile, taught me how to do a job from start to finish with a certain time restriction.

My plan with Ariana was to return to Chile after finishing my PhD since I had a position as an assistant professor at the School of Medicine that was offered to me when I finished my thesis at the Department of Biochemistry. I was eager to set up my laboratory and start doing research independently!

After two and a half years, Ariana was waiting for a baby and decided to return to Chile six months early to have our first child, Cynthia, whom she wanted to be a Chilean citizen. In a twist of fate, I received my PhD on May 3, 1968, the day my daughter was born.

I liked the competitive system in the United States. It opened my eyes to something I was not used to: if you are competitive, in the good sense of the word, you are rewarded. To be known, you must publish. The United States opened my appetite to be someone important as part of my education.

During my stay, I encouraged other Chileans, like Jorge Babul and Carlos Jerez, to pursue their PhD in Iowa.

Before returning to Chile, the Spanish Nobel laureate Severo Ochoa (Fig.4), a biochemist and molecular biologist, went to give a seminar in the capital of Iowa. Ochoa, a Spanish biochemist and enzymologist, was the recipient of the 1959 Nobel Prize for his discovery of the enzyme that enabled him to synthesize RNA. His work has had a significant impact on the field of biochemistry.

My thesis supervisor, who informed me about Ochoa’s seminar, stressed the importance of the event. If you are interested, it is crucial that you attend the seminar to gain insight into Ochoa’s significant contributions.

I agreed, and Thomas gathered the whole laboratory to go to Ames, where Ochoa gave a remarkable lecture to a large audience. Since he knew him well, he called me and said, “I will introduce you to him because he might like to talk to you in Spanish.”

We met, and Ochoa asked me, “What can I do for you?” I responded that he could help me get a grant to work in Chile. He told me that he was part of the Jane Coffin Child’s Foundation, which provided funding for projects on a competitive basis. If you present a good project, I will help you. I submitted a project, and it was accepted. I arrived in Chile with an American grant that ensured that I could start my laboratory there!!

RETURN TO CHILE

I returned to Chile in May 1968 and joined the Department of Biochemistry at the Faculty of Medicine to set up the laboratory. The building was old, but some laboratories had become free. I asked Professor Cabello, the director then, to let me use those spaces since no one was interested in them, and they required work to fit them out. He agreed, and I used part of the grant to remodel. However, the process was not without its challenges. The old building required extensive repairs, and the equipment was outdated. I engaged my father with his workers, who made the desks, painted the laboratory, and set everything up for me, overcoming these obstacles with their expertise and dedication.

For my research, I started something similar to what I had done in the United States but took another bacteriophage for a change. During my stay at the Biochemistry Department, I had a few students and some good collaborators. For a while, I shared the facilities with Pablo Valenzuela, who was returning from the United States.

As I was the first PhD in biochemistry to come to medicine from abroad, Hermann Niemeyer, Jorge Allende, Mitzi Canessa and others invited me to participate in creating the PhD in Biochemical Sciences or Biological Sciences in Chile. I worked with many well-known people in Chile and became Secretary General of the first PhD program in Chile. At the same time, I became Secretary General of the Biology Society of Chile, where I learned to organize courses and conferences. This involved working with many people, solving administrative matters that I had never done before, and overcoming challenges such as coordinating schedules, securing funding, and managing logistics. These activities also got me interested in science policy!

Between 1969 and 1970, I spent most of my time establishing the laboratory, which I loved: I learned to do everything from scratch and manage it, and that learning has served me throughout my entire career.

That was the suitcase I packed in those three years, a time when many may not have such opportunities: gaining knowledge in research, learning the ropes of a doctoral career, understanding the dynamics of working with secretaries, organizing scientific conferences and meetings, and gaining experience in scientific policy.

One of the most significant developments during this period was the arrival of two more children, Pamela and Juan Pablo. Their presence lit up our lives and added a new dimension to our family.

POSTDOCTORAL WORK IN CAMBRIDGE, ENGLAND

Jorge Allende’s encounter with John Smith at a Conference in London was significant. Smith, a prominent scientist at the globally renowned MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, a institution ranked second only to Harvard and home to four Nobel Prize laureates, expressed his interest in potential student applicants, saying, “If you have any student interested in coming to work, please let me know.”

Jorge arrived excited that someone from Chile could go to that place, where only Arturo Yudelevich, another biochemist of my promotion, had worked. Jorge told me that getting a scholarship to his laboratory was possible. Should we try?

Fortunately, the Welcome Trust, one of the largest foundations in the United Kingdom, approved the application and granted me a scholarship and tickets for my entire family. Ariana liked the idea of going to Cambridge, but she had to work, and with three children, hiring a nanny would be necessary.

We arrived in England in 1971, and Ariana was right; we couldn’t have worked without the nanny’s help, as her support was instrumental in allowing us to balance our professional and personal lives. Ariana got a job at Babraham in Cambridge, and I worked with John Smith (E. coli mutant suppressor tRNAs) and Sydney Brenner (Fig. 5) (Correlation between genetic and translational maps) for two years. Sydney, who received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2002, was a brilliant researcher and one of the most interesting people I met. My postdoc was wonderful as I created my network in Europe. The who’s who of science from all over the world came through the laboratory: Europeans, Americans, scientists from all countries, and always someone very important came to give a seminar a couple of times a week. These seminars were a platform for intellectual exchange and often led to insightful discussions about the latest developments in the field.

The laboratory, with its critical mass and state-of-the-art facilities, was not just a hub of innovation but a close-knit community of like-minded individuals. It provided a unique environment for young and established researchers, fostering creativity and pushing the boundaries of science. All were united in their passion for discovery, creating a sense of belonging and unity.

At that time, we were on the brink of returning to Chile when the seismic event of the military coup shook our plans. The uncertainty was palpable as we discussed our options; we had to decide what to do!

Despite my position in Chile, the coup’s new conditions left us with a weighty decision. Ariana’s stance was resolute, driven by her deep empathy and care: ‘I cannot bear the thought of subjecting our children to unnecessary trauma. I do not want them to grow up in that situation.

Given the uncertainty, we decided not to return to Chile. Ariana had family in France and suggested I try securing a job there. I applied to a prestigious laboratory in Strasbourg, and to my surprise, they offered me a job for three years.

When I shared my situation with Sidney Brenner, his response was a turning point. ‘Stay here; I will provide you with a five-year position as a researcher on the laboratory faculty. ‘I was deeply grateful for this opportunity and eagerly accepted the offer.

At that time, I had the honor and privilege of continuing my postdoctoral studies, now on chromatin, with Nobel Laureate Francis Crick, who, together with James Watson, determined the structure of DNA in 1953.

My postdoc was wonderful as I created my network in Europe. The who’s who of science from all over the world came through the laboratory: Europeans, Americans, scientists from all countries, and always someone very important came to give a seminar a couple of times a week. These seminars were a platform for intellectual exchange and often led to insightful discussions about the latest developments in the field.

As always, I still had a couple of years left of my contract at Cambridge, and Ariana began to worry. We did not know if they would renew my contract or what would happen to us. ‘Don’t worry,’ I said, ‘I’ll manage.’ I reassured her, accepting the uncertainty with a sense of determination and strength, which was a testament to our resilience.

One day, Brian Clark (Fig.6), a staff member, approached me and said, I have been offered the Head of the Division of Biostructural Chemistry position at Aarhus University in Denmark. I need people to build the department. I have a couple of positions as assistant professors and associate professors, and if you want, I can offer you a permanent Associate Professor position.

So, I turned to Ariana for her insight into this weighty decision. She said the reality is that we won’t be going back to Chile. Either we stay in England, in a role we enjoy but with no permanent positions or accept Brian’s offer. Finally, we decided that I should go to Aarhus to see the facilities.

During my visit to Aarhus, I was impressed by the department’s beautiful campus location and well-equipped facilities. Moreover, the presence of a prominent microbiologist at the University, Niels Ole Kjeldgaard, and the return of Kjeld Marcker from Cambridge to establish the Department of Molecular Biology were promising signs for the future.

Brian offered me a permanent associate professor position because my scientific profile fits within the structural biology program. It was a permanent position that would stabilise our family.

I resigned from my position in Chile, and we prepared for a life in Denmark.

MY PROFFESIONAL CAREER IN DENMARK

Biostructural Chemistry, Aarhus University

Denmark was a beautiful country with enormous facilities, an economic paradise. We came from Cambridge penniless because we hadn’t saved anything, so Ariana went to the bank and asked for a loan to buy a house. The process was surprisingly smooth, with the bank approving the loan based solely on my permanent job, without requiring any collateral. In six months in Aarhus, we had achieved what we could not do outside for many years: to have the infrastructure to start the family: a house by the sea and a school two blocks away.

At the laboratory, I became interested in proteins as I studied them in Cambridge, and early on, I received a call from a Chilean scientist – Rodrigo Bravo, who was doing postdoctoral work at Oxford University– expressing his interest in joining our research group in Aarhus. Rodrigo used microinjection methods to study frog oocytes and was familiar with two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2-D PAGE), a technique developed by Patrick O’Farrell at the University of Colorado in 1975. At the call, he said, “Look, I do not know you personally, but I know what you do. I have a fellowship from the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) and work at Oxford University, but I am unsatisfied with my current supervisor. Can I work with you?

I accepted because of his research experience, and Brian, who had connections with EMBO, arranged the transfer of Rodrigo’s fellowship to Arhus. This move led to a truly collaborative effort involving the whole laboratory to analyze the protein expression profiles of normal and transformed human and mouse cell lines and make comprehensive protein databases. Ariana, with her unique expertise from her previous work in Human Genetics at Aarhus University, took charge of organizing the cell-culturing facilities.

Our studies led to the identification of cytoskeletal, nuclear, cytoplasmic, and fluid proteins and to a comprehensive survey of organelle protein composition. We also explored understanding proteins’ behaviour under various physiological conditions, particularly in diseases like cancer. In 1981, we pioneered the development of the first comprehensive protein database of HeLa cell proteins, a move that would significantly advance the field.

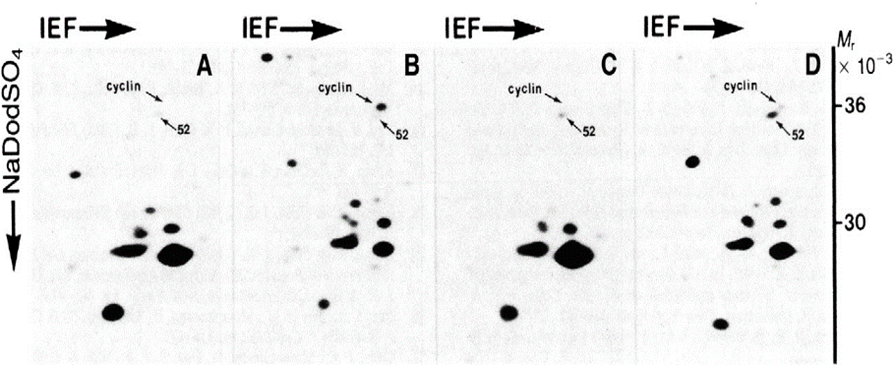

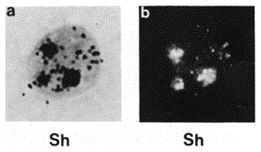

A key finding of our studies was the identification of Cyclin, a protein concurrently discovered by the E. Tans group as the Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA). We showed that Cyclin/PCNA reached its peak expression during the S phase of the cell cycle. The marker was either absent or present in very low amounts in normal non-dividing cells and tissues but was synthesized in variable amounts by proliferating cells of both normal and transformed origin (Fig. 7), underscoring its crucial role. All the available data indicated that this ubiquitous and tightly regulated DNA replication protein was pivotal to the pathway(s) leading to DNA replication and cell division. Cyclin/PCNA was the first protein we transitioned from a spot in a gel to a function, highlighting its paramount importance in our research.

We also demonstrated the coexistence of three major actin isoforms in a single Sarcoma cell.

Our comprehensive approach also gave us a global perspective on the field now known as Proteomics, underscoring the high significance of our work. In 2011, Fred Neidhardt, a respected figure in the field, acknowledged Leigh and Norman Anderson (Argonne National Laboratories), James Garrels (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), and myself (the lab) as one of the field’s founders ( https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201000780).

Our journey continued with a bold decision to use the cell as a test tube, a significant departure from traditional methods that sparked immense excitement in our team. This innovative approach involved injecting cells with various macromolecules using fine needles to study their function in their natural environment. However, we soon encountered a significant challenge: methods to determine their effect were limited, primarily based on microscopy. This realization underscored the urgent need for new technologies to study gene expression within living cells. Despite this outcome, our team remained committed to the new approach, demonstrating our dedication and perseverance in facing challenges.

During our time in Aarhus, Novel Laureate Francis Crick took a short sabbatical at the Institute (Fig. 8). His prominent standing in science and focus on Biostructural Chemistry enlightened the University and left a lasting impact. At that time, Arhus University created an open international environment and supported interdepartmental collaborations with strong support of Palle Finn Juul Jensen, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Aarhus University.

Institute of Medical Biochemistry (Aarhus University)

In 1986, I became a professor at the Institute of Medical Biochemistry at the Faculty of Medicine in Aarhus, the first professor who was not a medical doctor. After a decade as an associate professor, I finally had the chair and everything that came with it. It was the beginning of something more professional and organized. The Department was in a five-story building with many academic, technical, and workshop staff and laboratory facilities. Since there was a team of dedicated lecturers at the institute, I devoted myself wholeheartedly to working in the laboratory, creating a solid infrastructure for more proteomics, and ensuring the future of the field with the development and publication of comprehensive protein databases.

Thankfully, at that time, Denmark decided to align with global advancements, particularly in biotechnology, and invested in establishing research centers. This global alignment allowed us to apply and develop the Aarhus University Bioregulation Research Centre in 1989. The substantial grant we received was not just a financial aid, but a powerful catalyst that enabled us to transform the institute into a state-of-the-art research center.

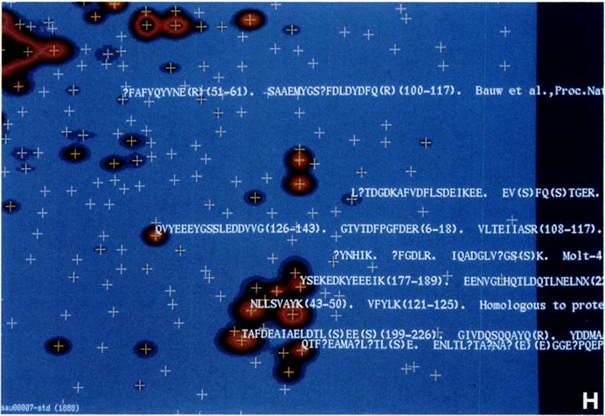

At that time, we prioritised the creation of computerised, comprehensive databases, a crucial tool in our research. These databases were linked to genome mapping and sequence information, providing a wealth of data for our analyses. We analysed clinically relevant samples (tissues and fluids) to study cancer and other diseases. We also published computerised comprehensive databases of Hela cells (Fig. 9), AMA cells, and keratinocytes and their link to genome mapping and sequence information. A significant achievement at that time was establishing a collaboration with J. Vandekerckhove and his group in Ghent on large-scale protein identification using microsequencing. This collaborative effort was a testament to the power of collective knowledge in advancing cancer research.

Since we used several cell biology techniques, I published Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook, a four-volume set containing comprehensive state-of-the-art protocols essential for the life sciences, together with Nigel Carter, Tony Hunter, David M. Shotton, Kai Simons, and J.V Small (Fig.10).

In parallel to the above studies, we collaborated for several years with clinicians to explore the immense potential of using proteome expression profiles of bladder Transitional Cell Carcinomas (TCCs) and Squamous Cell Carcinomas (SCCs) to identify protein markers that could impact diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. This comprehensive approach included cDNA array analysis, genome-wide studies of gene copy numbers, transcripts, and protein levels in pairs of noninvasive and invasive TCCs in collaboration with Torben Ørntoft in Aarhus.

Fresh specimens, including tumors, normal biopsies, and cystectomies, were systematically analyzed using 2D PAGE, and we established protein expression databases of TCCs and SCCs. These studies revealed several protein markers for TCC progression and a marker, psoriasin, that was produced specifically by SCCs and externalized to the urine.

To educate young scientists, we organised international courses in Aarhus (Fig.11) and abroad as innovative technologies and their application to biological problems became fashionable. The courses created a unique learning environment where the social aspect was crucial and instrumental to the learning process. This environment facilitated learning and provided ample opportunities for the students to meet each other and build their networks, emphasising the value of connections in the scientific community. The courses took place in the summer months, and 25 students from different European countries participated in learning new technologies in cell biology, including proteomics, for two weeks. We held these courses from 1982 to 1995. All these activities led me to meet many students and young scientists.

Arianas death

Ariana was about seven years older than me and was one year away from retirement. At that time, I was Chairman of the Council of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), and we had to attend the 25th anniversary celebration in Heidelberg. We decided to go quietly by car, and halfway there, before reaching Hanover, in the middle of the motorway, she had a severe attack with convulsions. A helicopter came quickly to take her to a nearby hospital, where she underwent many tests for two weeks, and that was when a very sad episode in my life began. We had to take things very slowly because Ariana was fragile and wanted to continue working at the same pace as before. I suggested to my daughter Pamela, a technical worker, that she come to work with us to look after her mother. She came, participated in the work in the laboratory and tried to make her day a little easier because sometimes she had episodes in which she lost her memory, did not know where she was and could fall.

After that first attack on the road, I prepared to stay home a little longer and ensure she was not alone. I was incredibly lucky to have the company and support of our daughter. In the meantime, we travelled to Chile, a little scared, but she endured the trip well. I remember feeling a rollercoaster of emotions during the journey, a mix of fear and hope that I’m sure many of you can empathize with. We arrived back in Denmark, but she was affected by the emotion of seeing her family and the idea that she might be unable to make another trip soon.

About two years later, in the summer of 1998, at the annual congress of the Federation of European Biochemical Societies (FEBS) in Copenhagen, which I was organizing, she had another strong attack and lost consciousness. She was rushed to hospital and died that night from a stroke. Our children, Pablo and Pamela, were our pillars of strength; their resilience and love inspired us during the most trying times. Cynthia, who was in Aarhus, managed to join us in time. We were grateful that they were able to see their mother before she passed.

We then returned to Aarhus to prepare for the funeral, with Brian Clark, who had brought us to Denmark, taking over the congress. We were deeply appreciative of his support during this difficult period.

Ariana’s death changed my life completely. We had many activities in common, and the whole laboratory was interconnected. It was a partnership, so it seemed impossible to start everything up again. I was left with a large laboratory without support. The task of rebuilding the laboratory was daunting, and I had to start redoing everything. Thanks to my daughter Pamela, I could move forward slowly.

The Danish Cancer Society (Copenhagen)

In 2000, I learned that the Danish Cancer Society, a highly influential organisation with 300,000 members, was searching for a scientific director to lead the Institute of Cancer Biology. This prestigious institution had a significant place in Denmark, making the opportunity to work for them highly sought after. Despite the fierce competition, I decided to apply for the position, not just as a career move but as a deep personal commitment to the fight against cancer, a cause that has touched many of us.

In 2001, I was offered the position and decided to focus on translational cancer research as the Cancer Society, a patient-centered organisation, recognised the need to foster collaboration between basic and clinical researchers.

Irina and Paul Gromov, pillars of the Laboratory at Medical Biochemistry in Aarhus, and Ingrid Detlefsen, my secretary, followed me. Within a short time, we recruited the technical staff, and Jose Moreira joined the team.

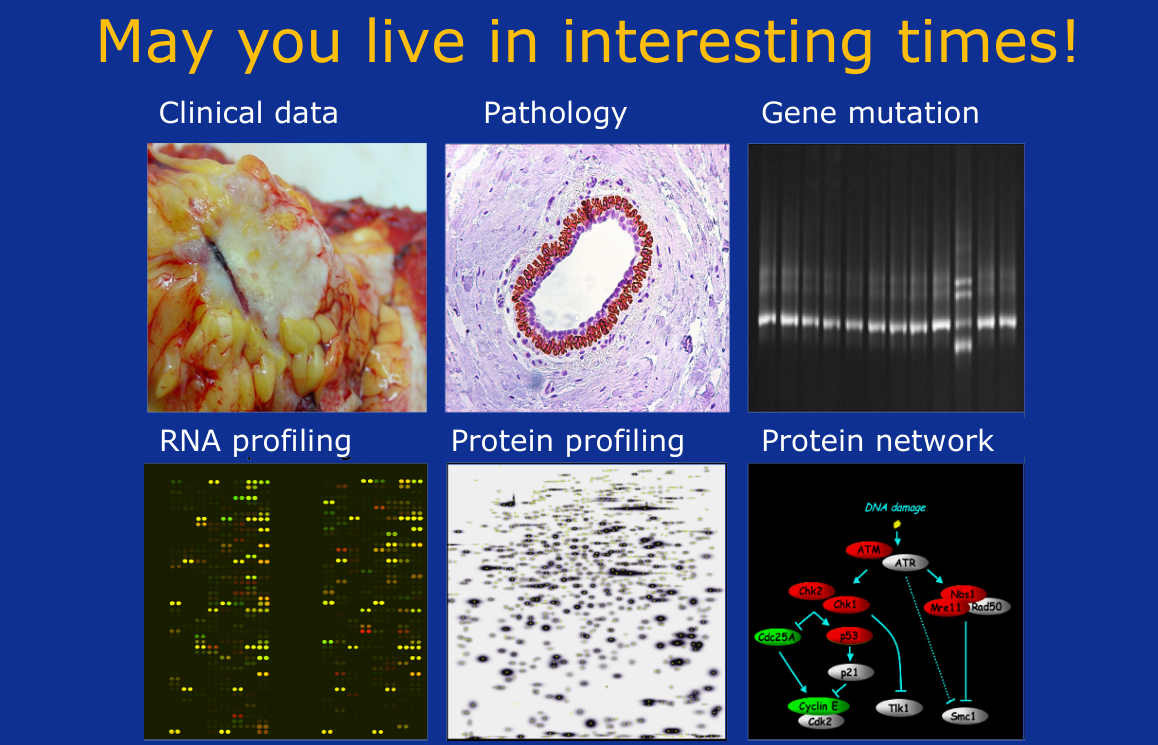

Our focus was on breast cancer, a disease of urgent concern in Denmark. At that time, approximately 3800 women were diagnosed with the disease annually, and an estimated 1200 lost their lives to it. This urgency drove our efforts and commitment to determine how best to apply omic technologies (Fig.12) to have a major impact on clinical practice, as these developments are likely to change the way cancer is diagnosed, treated, and monitored in the long term. In response to these challenges, the Danish Cancer Society catalysed the creation in 2002 of a multidisciplinary, multi-centre research environment, the Danish Centre for Translational Breast Cancer Research (DFCTB). DCTB hosted scientists working in various areas of preclinical cancer research (cell cycle control, invasion and microenvironmental alterations, apoptosis, cell signalling and immunology), as well as clinicians (surgeons, oncologists), pathologists, and epidemiologists. This integrated, mission-oriented, discovery-driven translational research environment was centered around the patient, with the goal to conduct research to improve the survival and quality of life of breast cancer patients, a mission that inspired us every day.

Early in 2003, Teresa Cabezon, a respected colleague in Biochemistry at the University of Chile, who had worked at GSK in Brussels at the Department of Research and Development since 1978, joined the team. She had contributed significantly to developing the recombinant Hepatitis B vaccine and was eager to join the team. Teresa’s professional journey took her from Brussels to Copenhagen, and it was in these vibrant cities that we decided to intertwine our lives (Fig.13).

An important outcome of our work was the pioneering proteomic characterisation of the tumour interstitial fluid (TIF) perfusing the breast tumour microenvironment. This novel resource opened new avenues for biomarkers and therapeutic target discovery (Figs 14 and 15). We collected TIFs from small pieces of freshly dissected invasive breast carcinomas and analysed them by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in combination with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry, Western immunoblotting, and cytokine-specific antibody arrays. These findings had the potential to significantly influence future research in this field.

For the first time, our comprehensive approach offered a detailed snapshot of the TIF protein components consisting of more than one thousand proteins, either secreted, shed by membrane vesicles, or externalized due to cell death. These proteins were produced by the complex network of cell types that form the tumor microenvironment. At that time, we identified about 300 primary translation products, including, but not limited to, proteins involved in cell proliferation, transformation, invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis, inflammation, protein synthesis, energy metabolism, oxidative stress, actin cytoskeleton assembly, protein folding, and transport.

Cellular function categories assigned to the known proteins included but were not limited to ion transport, cell motility, transporter activity, protein transport, signal transduction, response to oxidative stress, immune response, energy pathways, regulation of gene expression, proteolytic pathways, protein metabolism, maintainers of cytoskeleton organisation, cell-cell signalling, regulation of cell-cell communication and regulation of cell growth. We are deeply grateful for the unwavering support of Pathologist Fritz Rank, who was instrumental in our research.

In 2007, I launched Molecular Oncology with the invaluable support of FEBS (Fig.17). The journal has been a platform for a diverse array of articles, covering basic, translational, and clinical cancer research, as well as science policy articles that explore emerging cancer research concepts in diagnosis, prevention, and care. It has also been instrumental in recognizing the growing importance of science policy activities in cancer. The initial support from Ian Mowbray and Jose Moreira was crucial and greatly appreciated in establishing the journal.

In 2011, I retired from bench work to dedicate full time to cancer science policy activities, first with FEBS in 1999 and thereafter with ECCO and the European Academy of Cancer Sciences (EACS).

SCIENCE POLICY ACTIVITIES IN BASIC AND TRANSLATIONAL RESEARCH

1. CREATION OF THE EUROPEAN RESEARCH COUNCIL (ERC)

The European Research Area (ERA)

At the Lisbon Summit of Heads of State and Government of the European Union (EU) in March 2000, science was for the first time politically endorsed as a major driver for the future of the EU alongside the deployment of information technologies and their promise of an “information society”. The “Lisbon Strategy” announced a bold agreement by all EU States to “work towards making the EU the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustained economic growth, providing more jobs and achieving greater cohesion” Progress in the basic sciences was recognised as important as innovation, a key point encouraging the audience to push boundaries and explore new frontiers. Moreover, bringing together, as convergent players, R&D institutions and programs at national, intergovernmental, and EU levels was set as a major objective.

This promise was followed by a commitment at the Barcelona EU Summit in 2002 to increase (public and private) the R&D expenditure in the Union to 3% of the GDP by the year 2010. For the first time, the heads of government proposed a substantial increase in the EU budget for research. This move stimulated the scientific community and fostered a spirit of collaboration and engagement in science policy issues to achieve the ERA goals, a concept conceived by Commissioner Phillip Busquin because of the political objectives set by EU governments. Busquin developed the idea of ERA as a dynamic convergence space for all European science and technology actors. Such a concept provided a framework for setting political priorities for EU science policy ( https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategyresearch-and-innovation/our-digital-future/european-researcharea_en).

FEBS, a leading organisation in European life sciences with nearly 40,000 members spread across 36 Constituent Societies in Europe, was at the forefront of recognising scientists’ societal responsibility and was committed to structuring and amplifying the input of the biochemical community to science policy across the life sciences and played a pivotal role in shaping the direction of European research and development (1- 3).

Towards this aim, in 1999, as Secretary-General of FEBS, I proposed to the Executive Committee (Fig.18) the creation of a Science and Society Committee (2). This forward-looking Committee was important as it would serve as a bridge between scientists and society and identify and address issues arising from new research developments. Its establishment would not just mark a crucial step but a beacon of hope in the evolution of life sciences, paving the way for a more integrated and impactful future. Federico Mayor, former Director General of UNESCO (1987-1999), was appointed Chair of the Committee in July 2001. Federico was exceptional, with a clear vision, political wisdom, courage, and a deep sense of loyalty. One of the Committee’s tasks

Recognising the increasingly multidisciplinary nature of research in life sciences, I also emphasised to the Executive Committee the urgent need to collaborate with other international organisations to achieve a global vision. The Executive Committee highly supported this proposal, particularly by Joan Guinovart, a very close colleague of Federico Mayor. As a result, at the Council meeting in Nice in June 1999, I announced that I was in discussions with the European Molecular Organisation (EMBO), the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), and the European Life Science Organisation (ELSO) to establish a Forum for life sciences in Europe with a global impact. This collaborative effort underlined the unity and shared vision in the scientific community, a sense of belonging and unity that we all shared.

Shortly thereafter, at a meeting hosted by EMBO at the EMBL in Heidelberg, a group of prominent life scientists agreed to work towards creating the European Life Sciences Forum (ELSF). This decision, made in May 2000, was a significant step towards our goal. Accordingly, a small governing body was appointed consisting of Frank Gannon, Fotis Kafatos, Kai Simons, and myself as President (Fig. 19). Luc van Dyck joined as manager six months after the organisation was created. The secretariat was set up at the EMBL/EMBO facilities in Heidelberg. With their generous support, EMBL, EMBO, and FEBS offered to cover a large fraction of the expenses for 3 years, providing us with a stable and secure financial foundation and ensuring ELSF’s future.

The ELSF’s preliminary activities involved identifying and contacting key stakeholders, establishing close connections with Commission officials in Brussels, and providing input to Framework Programme 6 (FP6), the EU’s multi-annual research and technology development program (2002–2006). The ELSF experienced rapid growth with other disciplines and organizations as the discussions progressed, highlighting its collaborative and inclusive approach to research and technology development. In 2004, ELSF broadened its base to include all natural sciences, social sciences, and the humanities and in 2004 launched the Initiative for Science in Europe (ISE) ( https://initiative-se.eu/about/).

José Mariano Gago, the first president (Fig.20), truly steered the organisation’s course and left an indelible mark on the ISE’s history. Our enduring collaboration with José Mariano began at the FEBS Congress in Lisbon in 2001. It was a testament to our unwavering unity and shared dedication to science policy issues, which left a lasting impact on the field.

The ISE, a testament to the ELSF’s inclusive approach, served as a unifying force, bringing together European learned societies and scientific research organisations across all disciplines and research sectors. It actively involved researchers in shaping and implementing European science policies, thereby playing a crucial role in the development of European science. The organisation’s advocacy for robust, independent scientific advice to develop broader European policies has been pivotal, as has its championing of disruptive, excellence-based funding programs for scientific research, including promoting the ERC.

Creation of the ERC (2-4)

The Royal Academy in Sweden, a key player in the European research landscape, proposed the creation of the ERC in 2001. This proposal was later deliberated at a landmark conference in Copenhagen in October 2002 during the Danish presidency of the Council. The event, titled “Towards ERA: Do we need a European Research Council?” was attended by politicians, representatives from ministries, European research councils, and a few scientists, including myself, representing the ELSF. This marked a significant milestone in the ERC’s journey.

Denmark was interested in taking this program further, which undoubtedly required a big effort. They discussed what type of research should be funded, whether it was necessary, and its potentially transformative impact on the ERC, a prospect that filled us with optimism and hope for the future. Since the scientific community was not properly represented at the meeting, I proposed on behalf of the ELSF to organise a follow-up meeting to gather the scientific community’s opinions and provide a forum to nurture and discuss the ERC initiative over the following years.

The Copenhagen meeting report was sent to the EU research ministers, who, at their November 26 meeting the same year, agreed to embark on a collaborative journey. This journey involved exploring options for creating an ERC in cooperation with relevant national and European research organisations. The collaborative nature of this approach ensured that all stakeholders were part of the decision-making process, fostering a sense of shared responsibility and inclusion.

To solidify the concept of an ERC before the end of the presidency, the Minister for Science, Technology, and Development, Helge Sander, took a crucial step in October 2004. He formed a small committee, the ERC Expert Group (ERCEG), which was a significant and commendable effort. At the end of the Danish presidency of the Council, I proposed Federico Mayor, former Director General of UNESCO and Chair of the FEBS Science and Society Committee, to Chair the ERCEG Group (Fig 21). His extensive experience in scientific policies, gained during his tenure at UNESCO and work in FEBS, made him a highly qualified candidate for this significant position. Federico, who prioritised science and the welfare of society, was the perfect fit for the job, given his qualifications and dedication to the field.

Federico received outstanding assistance from Mogens Flensted Jensen, Vice-Chair of the Group, and other members of the ERCEG in preparing the report. Moreover, the exercise benefited greatly from consultations with scientific organisations, representatives of research ministries, and individual scientists.

The ERCEG group, under Federico Mayor’s leadership, was pivotal in supporting the ERC and making the EP and the EU Council of Ministers accept FP7 for the European Union’s support for research, with the ERC as a flagship component. José Mariano Gago’s leadership was also instrumental in creating the ERC, as he had extensive and influential connections with the Competitiveness Council, leaving an enduring and significant impact on the program.

The final ERCEG report was presented to Minister Sander on the 15th of December 2003 ( https://erc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document/file/expert_group_final_report.pdf) recommended the establishment of “a new European dimension for research funding, the ERC that will foster collaboration and competition among European researchers, allowing them to compete based on excellence”. The report also addressed the ERC’s autonomy, funding, accountability, and governance issues. It stressed that political commitment from the EU would be necessary to ensure a fully operational ERC at the very start of the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). The potential of the ERC to foster collaboration and competition is not just exciting but also significant, underlining the impact it can have on all stakeholders.

In 2004, a high-level expert group was established to explore the possibilities of creating an ERC. This group and several other expert groups, such as one commissioned by the European Science Foundation, another charged with analyzing the economic implications of the Lisbon Declaration, and a high-level group commissioned by the EC, all reached a unified conclusion. They agreed that the EU should establish an institution to support frontier research.

In July 2005, before the first informal Competitiveness Council under the UK Presidency, the ISE sent a letter to the Research Ministers of the 25 EU Member States, the EC, and European Parliament (EP) members. In this letter, the ISE called for an autonomous ERC with a budget strategically aligned with the needs and aspirations of the Lisbon agreement, demonstrating the foresight and planning in EU research policy. This letter was signed by 42 organizations related to the ISE, marking a significant improvement in EU research policy.

The same year, the EC’s Director General for Research Achilleas Mitsos gave a speech at an ISE‐organised meeting where he re‐interpreted the EU laws. He emphasized that EU‐wide competition, including basic research, met the necessary precondition of “added value” for the member states. Thus, the way was open to include the ERC in FP7, and this formal inclusion in 2006 marked a significant step in the field’s evolution.

Under Federico Mayor’s influential leadership, the ERCEG group was pivotal in supporting the ERC, a program of utmost importance in European research, and making the EP and the EU Council of Ministers accept FP7 for the European Union’s support for research, with the ERC as a flagship component. José Mariano Gago’s leadership was also instrumental in creating the ERC, as he had extensive and influential connections with the Competitiveness Council, leaving an enduring and significant impact on the program, underscoring the vital role of the ERC in European research funding.

Today, the ERC ( https://erc.europa.eu/homepage) stands as the premier European funding organisation for excellent Frontier research. It serves as a reassuring beacon for the future of European research excellence and instills optimism and hope in the research community.

References

1. Van Dyck, L., 2002. A new partnership between science and politics. European scientists ought to adapt to new research policy paradigms. EMBO Rep. 3, 1110–1113.

2. Celis JE, Gago JM. 2014. Shaping Science Policy in Europe. Mol Oncol 8, 447–457.

3. Frank Gannon, 2017. The ERC: from before then to anniversary celebrations, EMBO reports, 18, 11,1873-1874.

4. König T. The European Research Council. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2017.

2. THE EUROPEAN CANCER MISSION

Even though ERA covered all areas of science, it was clear that Europe needed to deliver the treatments and diagnostics expected by healthcare professionals and citizens. As a result, Commissioner Busquin, with the support of the European Parliament (EP), proposed in 2002 the creation of the European Cancer Research Area (ECRA) at the ‘Towards Greater Coherence in Cancer Research’ conference ( http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-02-408_en.htm). European cancer research was fragmented, and there was a need to create a common European strategy for cancer research. In his concluding remarks, Commissioner Busquin stated, ECRA will be what you make of it’. At this point, cancer became one of the priorities in the Six Framework Program (FP6), and for the first time, an FP could explicitly support clinical research [1, 2].

Encouraged by the outcome of the conference as mentioned above, as well as by further discussion with the cancer community and the EP, Commissioner Busquin in 2004 established a Temporary Working Group to identify ways to coordinate cancer research in Europe better and identify areas and research topics where there was a certain level of activity in the Member States that could benefit from improved coordination at the EU level. The group, chaired by M. Wim Van Velzen, a member of the EP, and composed of clinicians, basic researchers, health authorities, funders, patient organizations, and industry (Kari Alitalo, Harry Bartelink, Jose Baselga, Josep Borras, Peter Boyle, Julio Celis, Pier Paolo di Fiore, Margaret Frame, Josep Jiricny, Lucas Gianni, Les Hughes, Susan Knox, David Lane, Alex Markham, Francoise Meunier, Herbert Pinedo, Thomas Tursz, Dominique de Variola, and Otmar Wiestler) was asked to identify barriers omitting effective collaboration, as well as ways to promote development of partnership among the Member States. Following the recommendations of the Working group, the European Commission (EC) launched a call for proposals integral to FP6 in 2004 that led to the funding of the EUROCAN+Plus project in October 2005, a 2 year project coordinated by Peter Boyle, then Director of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon France ( https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22274749/).

The project recommended the creation of a small and independent European Cancer Initiative (ECI) and underscored the importance of Comprehensive Cancer Centers (CCCs), patient-focused entities connecting research and education with therapeutics/care and prevention. CCCs are crucial in bridging research with the healthcare system, integrating every stage of the cancer research continuum to perform translational research.

At the end of the EUROCAN+Plus project, FP6 had ended, and FP7 had already started, leaving a gap that needed to be bridged if the translational research platform proposal were to become a reality. FPs do not allow continuity, and as a result, other options had to be explored.

Stimulated by the EUROCAN+Plus project’s outcome, the Directors of16 leading European cancer centers met in Stockholm in September 2008, at Ulrik Ringborg’s invitation, to define the “European platform for translational cancer research” concept and discuss steps towards its implementation (3, 4). Ulrik had extensive experience in translational research and had been President of the Organisation of European Cancer Institutes.

The Stockholm Declaration signaled a paradigm shift in cancer research, catalysed by the dedication and collective vision of basic and clinical researchers who agreed to use a coordinated and concerted approach to implement a platform for translational cancer research by bringing together CCCs.

A manifesto called “the Stockholm Declaration” was published to mark their commitment to working towards its realisation, clearly stating their intention to join forces and share resources ( 3, 4). This key event, as well as meetings funded by cancer organisations, led to the funding of the EurocanPlatform Network of Excellence in 2011 (FP7).

Several informal meetings took place in 2008 to coordinate and prioritize the activities of the Stockholm group. The first steps towards making the Stockholm Declaration a reality occurred at the ‘Turning the Stockholm Declaration into Reality: Creating a Worldclass Infrastructure for Cancer Research in Europe’ meeting held at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) headquarters in Paris in 2008. The Danish Cancer Society, the ISE and UNESCO jointly sponsored the conference. It was attended by scientists, clinicians, policymakers, managers, patient organizations, and representatives from industry. At this meeting, former Commissioner Busquin indicated that scientists must frame the challenge in such a way that it targets the specific responsibilities of the EC as separated from the national duties. Health care is the responsibility of the Member States, while research is a European competence over which the Commissioner can legislate and allocate funding. For translational cancer research, the necessary integration of healthcare and research, the objective of the CCC, requires new ways of collaboration between healthcare and research.

Commissioner Busquin suggested that winning the support of ERA stakeholders (Fig.22) was essential and urged the cancer community to act quickly, as financial perspectives would be discussed in 2009. Hence, the possibility of applying to FP7 to achieve continuity arose.

A very encouraging outcome of the meeting in Paris was that the cancer community was perceived as a well-structured group and a dependable partner/stakeholder for planning future research activities, including setting priorities for upcoming calls within the framework programs. At this point, connecting FP7 was on the horizon!

At the UNESCO Conference, it was also clear that we had to bridge the gap between science and policy and ECCO, with its constituency of over 50 .000 professionals in oncology, broad international representation, multidisciplinarity, and its prestigious bi-annual congress, seemed uniquely positioned to channel the voice of the whole cancer community and to provide a platform for debating European cancer policy issues that may benefit the patients as well as society as a whole. As a result, I proposed to ECCO both the creation of the Science Policy Committee in 2008, supported by well-known policymakers and advisors (Philippe Busquin, Jose Mariano Gago, Frank Gannon, Federico Mayor Zaragoza, and Peter Lange) and the establishment of the European Academy of Cancer Sciences (EACS) at the ECCO 15 – ESMO 34 Congress in 2009. The EACS was to enhance the education of professionals working in cancer care and research by exchange, collaboration, and training of MDs and PhDs involved in biological, translational and clinical cancer research, stimulate the two-way traffic between bench and bedside, ensure consistent authoritative scientific input in policies regarding cancer (think tank role), and promote European initiatives for translational research that would have a major impact on cancer prevention, early diagnosis and treatment. Key supporters of the Academy included Michael Baumann, Alexander M.M. Eggermont, Tim Hunt, Georg Klein, David Lane, Paul Nurse, Thomas Tursz, Umberto Veronesi, Harald zur Hausen, and Jose Mariano Gago. The first President of the EACS was Alexander Eggermont, and I chaired the Science Policy Committee.

Stemming from the EUROCAN+Plus project and the support from cancer organizations, the cancer community, and policy advisers, the EurocanPlatform Network of Excellence, led by Ulrik Ringborg, was funded by FP7 in 2011 ( https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/260791/reporting).

The project engaged 28 European cancer centers, 11 Member States, and five large scientific organizations, eCancer.eu, ECCO, the European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC), the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), and the Organization of European Cancer Institutes (OECI). The task was to create a translational cancer research platform to promote innovation in prevention, early detection, and therapeutics, with a focus on personalized medicine.

One of the main achievements of the EurocanPlatform was the creation of Cancer Core Europe in 2014 (5) proposed by O. Wiestler and spearheaded by A. Eggermont, who used a bottom-up approach to initiate the process as recommended in the Stockholm Declaration. The initial centers participating in the Cancer Core were Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, the Cambridge Cancer Centre, the Karolinska Institutet, the Netherlands Cancer Institute, the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology and the German Cancer Research Centre with its CCC, the National Centre for Tumor Diseases. Later, the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori joined the platform. Most centers are designated CCCs, i.e., institutions where prevention and treatment are integrated with research and education.

The Cancer Core Europe’s goal of linking scientific discovery from bench to bedside included the creation of a virtual ‘e-hospital’ to enable joint research programs with a shared research infrastructure platform aimed at personalized/precision cancer medicine: (a) quality assurance and sharing of data from clinical trials; (b) molecular tumour boards for stratification of patients for clinical trials; (c) integrate diagnostic procedures including imaging; (d) expand next generation clinical trials to reach the necessary critical mass; anticancer agents and immunotherapy; and (e) education and training; legal and ethical issues to facilitate international research collaborations.

The late Portuguese minister Jose Mariano Gago’s vision, leadership, and support were instrumental during the various phases of the EurocanPlatform Consortium, including the creation of Cancer Core Europe, as he continuously communicated with Commissioner Moedas.

Following the initial success of Cancer Core Europe, Christopher Wild, director of IARC, spearheaded the creation of Cancer Prevention Europe (CPE) (6). Today, CPE is a reality composed of 10 leading European research organizations. Cancer Core Europe and CPE link the therapeutic and prevention geometries. Together, they will provide a virtual infrastructure that, in concert with other networks of cancer centers, will serve as a hub and an engine to coordinate and optimize joint cancer research efforts across Europe. It will also facilitate rapid advances in knowledge and their translation into better cancer treatment, care, and prevention. The creation of Cancer Core Europe and CPE may again initiate a discussion to establish an ECI in the future.

Jose Mariano, who sadly passed away on September 17, 2015, played a pivotal role in science policy activities. His influence extended even after his passing, as he had already worked to ensure Manuel Heitor’s appointment as Minister of Science, Technology, and Higher Education, thereby providing the continuity of his work and reassuring us about the future of science policy. My collaboration with Manuel began in early 2016. Together, and in partnership with Ciência Viva and others, we established the “Gago Conferences on European Science Policy”. This initiative, which provided an international platform, significantly contributed to the global debate on emerging research and innovation policy issues in Europe, a testament to Mariano’s international influence and impact.

In July 2017, the ‘Lamy Group’ appointed by the Commission to maximize the impact of EU Research and Innovation programs, suggested a mission-oriented approach in Horizon Europe to address global challenges. Commissioner Moedas was initially inclined to a brain mission, but I convinced him to prioritize cancer based on the activities and aims of Cancer Core Europe, to which he agreed.

Accordingly, together with former Minister Dainius Pavalski as members of the RISE-High-Level Group that advised the Commissioner, we proposed in 2017 a cancer mission that stated that by combining innovative prevention and treatment strategies in a sustainable state-of-the-art virtual European cancer center/infrastructure, it will be possible by 2030 to achieve long-term survival of three out of four cancer patients in countries with well-developed healthcare systems [7]. In the long term, primary prevention will modify the increasing cancer incidence. Furthermore, the proposed concerted actions will pave the way to handling the economic and social inequalities in countries with less developed systems. These efforts will also ensure that, in the long run, science-driven and social innovations reach patients across the healthcare systems in Europe. EACS members contributed to the preparation of the proposal, in particular Ulrik Ringborg its Secretary General.

In February 2018, the mission on cancer was thoroughly discussed at the first Gago Conference on ‘European Science Policy, a collaborative effort centered on cancer research in Europe and policy perspectives. This significant event took place at the i3S in Porto, Portugal, under the auspices of the Portuguese Agency for the Promotion of Scientific and Technological Culture, Ciência Viva, and with the support of the Portuguese Ministry for Science, Technology, and Higher Education Manuel Heitor, a great supporter of the cancer mission (8) ( https://www.cienciaviva.pt/gagoconf/1st-edition/) (Fig.23).

Among the issues addressed, Ulrik Ringborg, Secretary-General of the EACS, emphasized that a Mission on Cancer must cover the entire cancer research continuum for both prevention and therapeutics. The meeting also presented a unified view about establishing high-quality networked infrastructures to decrease cancer incidence, increase the cure rate, improve patient survival and quality of life, and ideally deal with research and care inequalities across the EU (9). Closing the meeting, Commissioner Carlos Moedas, a key figure in European science policy, reiterated his staunch support for the Cancer Mission currently being implemented in Horizon Europe, instilling confidence in the future of cancer research in Europe (Fig.24).

In addition, Commissioner Moedas invited Professor Mariana Mazzucato to provide strategic recommendations to maximize the impact of the future EU Framework Program for Research and Innovation through mission-oriented policy. Mariana Mazzucato stimulated policy debate at both national and EU levels continuously and proactively and outlined the main issues underlying the implementation of missions ( https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5b2811d1-16be-11e8-9253-01aa75ed71a1/language-en ). ( https://www.pas.va/content/dam/casinapioiv/pas/pdfvari/statements/statement_strategies_cancer.pdf ).

In October 2018, the European Competitiveness Council discussed preliminary ideas concerning missions based on a non-paper presented by the Commission. Five potential mission areas were addressed, including curing pediatric cancer by 2030.

In November 2018, the broad cancer mission was discussed at a Conference that took place at the Vatican City, ‘A mission-oriented approach to cancer in Europe: Boosting the impact of innovative cancer research’ jointly organized by the EACS and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. The Conference concluded that, as cancer is predominantly a disease of aging, focusing on the 0.6% of all cancer patients in the 0–19-year age group will severely compromise a mission’s scientific, social, and economic impact. Moreover, a mission limited to pediatric oncology would not address research on prevention and early detection, which are fundamental to progress against cancer overall. Pediatric oncology should be an essential component of a mission covering all cancers.

In December 2018, it was agreed that a general cancer mission should replace the pediatric cancer mission. The debate among Member States at the level of the Competitiveness Council among Research Ministers was central to this decision.

In February 2019, the European Competitiveness Council approved five mission areas following the Commission proposal: climate change, cancer, oceans, carbon neutrality, and food.

In June 2019, the EACS supported Miklós Kásler, former head of the National Institute of Oncology Budapest and Minister of Human Resources in Hungary, to create the Central Eastern European Academy of Oncology, connecting 21 countries to promote cooperation in the fields of cancer prevention, treatment, and care to decrease present inequalities.

In July 2019, Commissioner Moedas appointed Nobel laureate Harald zur Hausen, a member of the EACS, as Chair of the Horizon Europe mission board for cancer to lead the EU’s research mission on cancer following a recommendation from Julio Celis.

In September 2019, the Mission Board held its first meeting.

In October 2019, the ministers responsible for research in Germany, Portugal, and Slovenia signed the declaration ‘Europe: together against cancer’ ( https://www.dekade-gegen-krebs.de/de/wir-ueber-uns/aktuelles-aus-der-dekade/_documents/deklaration-europa-gemeinsam-gegen-krebs ); and Professor Walter Ricciardi substituted Professor Harald zur Hausen due to health problems.

In October 2020, the declaration on the need to promote cancer research in Europe, ‘Europe united against cancer’, was signed on October 13 by Germany, Portugal, and Slovenia, under the Council Presidency Trio of the EU and within the scope of the German Presidency of the Council of the EU. It aimed to guide future directions for public and community support for research activities and to encourage stronger collaboration with health systems across Europe.

In December 2020, the Mission Council gave the final recommendations to the European Commission.

In February 2021, the EC created Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan (EBCP). The Cancer Plan is structured around prevention, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment, and improving quality of life ( https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_342 ). Through EBPC, the Commission will deal with all aspects of the disease pathway. It also plans to collaborate with the USA Cancer Mission.

In May 2021, the Porto European Cancer Research Summit brought together key stakeholders to align research with the Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan and Cancer Mission . It focused on creating high-quality, networked infrastructures, promoting translational research, improving patient outcomes, and tackling care inequalities, culminating in the Porto Declaration on Cancer Research (9).

In September 2021, the MoC was launched by publishing its Implementation Plan. The new goal stated, ‘By 2030, more than 3 million lives saved, living longer and better’. The mission objectives included understanding cancer, prevention and early detection; diagnosis and treatment; quality of life for patients and their families; and equitable access. From 2024, the MoC “UNCAN.eu” will establish a digital platform where researchers can access and share high-quality data to better understand cancer. EBCP, on the other hand, has launched several projects involving networking, such as CraNE (organization and framework for a European network of CCCs), JANE (European networks of expertise).

Since the Porto Conference, several meetings have discussed the above issues (10,11). In particular, the fifth Gago Conference at the DKFZ in Heidelberg in 2023 (Fig.25) and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and EACS conference in 2023 have provided an international overview of the increasing cancer problem (Fig. 26) ( https://www.pas.va/content/dam/casinapioiv/pas/pdfvari/statements/statement_strategies_cancer.pdf ).

Today, Europe´s Beating Cancer Plan (EBCP) and the Mission on Cancer (MoC), implemented in 2020-21 by the European Commission, offer to organise cancer therapeutics/care, prevention, and research to decrease fragmentation ( https://www.nfp4health.eu/otherinitiatives/eu-cancer-beating-plan-eu-cancer-mission/). They will make high-quality and innovative cancer therapeutics/care available for all patients, regardless of their background or circumstances, increase the critical mass of translational research, and establish the necessary research infrastructures to promote evidence-based and cost-effective cancer therapeutics/care and prevention. These initiatives, with their potential to revolutionise cancer treatment and prevention, bring hope and optimism for a future where cancer is no longer a major threat.

On October 16 2024, former Portuguese minister Manuel Heitor published the High-Level Group report Align, Act, Accelerate on the mid-term review of Horizon Europe ( https://research-innovationcommunity.ec.europa.eu/events/5cNLsztvwo0UYN2HeL9UDw/overview). This significant milestone report stressed the crucial role of advocacy in the future, alongside the urgent need for deeper collaboration to fully harness the potential of European science and technology. This emphasis on cooperation underscores the importance of collective action in driving the future of European science and technology. Among several recommendations, the report urged creating a European Societal Challenges Council to steer collaborative research.

Speaking to the cancer community, Heitor highlighted the urgent need to create a robust Framework Programme and referred to the ERC as a shining example of European success in science and technology. He considered mission-oriented research programs important in the future, and cancer quality-assured CCCs for translational cancer research collaboration, including outcomes and health economics research, should be prioritised. He also underlined the significant role of startups in commercialising research outcomes, a key factor in driving economic growth and innovation. This emphasis on startups should make the audience feel the potential for economic growth and innovation. He suggested that the EACS should be more politically active and asked us to tackle issues related to the organisation and accreditation of CCCs.

Ekaterina Zaharieva, commissioner-designate for startups, research, and innovation, supported the Heitor group’s recommendations on collaborative research and public-private partnerships. She also endorsed the EIC, a key player in the report’s vision for the future of European science and technology.

On May 22-23, 2025, The Pontifical Academy of Sciences (PAS) and the European Academy of Cancer Sciences (EACS) hosted a Conference on Cancer Research, Healthcare and Prevention: Structuring Translational Research to Increase Innovation and Reduce Inequalities that took place at the Casina Pio IV.

The focus of the conference was on P4 Cancer Medicine (Predictive, Preventive, Personalized and Participatory), a comprehensive strategy encompassing Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) research, aiming to enhance the well-being of patients and individuals at risk. Addressing the cancer problem requires two key elements: translational cancer research and the development of relevant infrastructures. A Comprehensive Cancer Centre (CCC) acts as an innovation hub by integrating high-quality, multidisciplinary therapy and care, with healthcare-dependent prevention, research, and education. The United States has been at the forefront, providing quality-assured CCCs and the Cancer Moonshot for strategic cancer research. The EU has followed with the European Research Council for basic research, the European Innovation Council to boost disruptive innovation, and two EU initiatives on cancer, Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan (EBCP) and the Mission on Cancer. The increasing complexity of cancer biology and technologies presents both a research challenge and a healthcare demand. For most patients, a CCC is not available. A critical discussion focused on quality assurance of healthcare outside the catchment area of a CCC and involving patients in clinical research. The strategic deployment of resources to support collective healthcare efforts and research aimed at reducing the cancer problem was discussed with representatives from the United States, EU, Africa, South America, China, India and Taiwan. Analyses of translational cancer research have revealed important gaps in implementing innovations, assessment of clinical effectiveness, HRQoL, outcome and health economics research. The increased release of new anticancer agents over the last 25 years, accompanied by insufficient information on clinical benefits, presents both an economic and ethical problem. Direct healthcare costs have increased due to expenses for anticancer agents for the treatment of patients with incurable diseases. Evidence-based treatment based on HRQoL research is an unmet need. Basic/preclinical research aimed at increasing the cure rate should identify new, broader targets for therapy and develop extended diagnostic technologies for stratifying patients, to inform innovative clinical trials.

Present research strategies convert cancer to a chronic disease, a growing burden for the healthcare systems. The increasing complexity of cancer biology and technology, the growing need for translational cancer research, and the demand for supporting infrastructures underscore the importance of international collaborations between CCCs. However, funding for cancer research is not currently aligned to reduce the cancer problem. While public funding for cancer research doubled between 2005 and 2024, the pharmaceutical industry’s spending on cancer research increased tenfold. Increasing funding by public and non-profit funding organizations is mandatory. Education is another significant need, but it is currently fragmented and underfunded. The last session of the conference summarized the strategies in a Statement with a strong emphasis on global collaboration addressing the growing cancer burden and pronounced inequalities. Expanding partnerships and fostering innovative, multidisciplinary approaches to cancer prevention, therapeutics/care, as well as research, are not just urgent but essential steps towards reducing incidence, increasing cure rates and enhancing the well-being of cancer patients. Data-driven cancer medicine is currently under development, and modern communication technologies for diagnostics may facilitate interactions across geographical distances. A global cancer research agenda can become a model of solidarity, sustainability, and ethical responsibility.

Today, Europe leads the fight against cancer with a unique cross-border approach that differs from past US efforts, in particular the Nixon “War on Cancer” (12) and the Obama “Cancer Moonshot” (13). Multidisciplinary collaborations across the European Union provide leadership that transcends nationally focused strategies and funding. Over the past decade, the European cancer community has built expertise, deepened science policy engagement, partnered with patients, and expanded infrastructure and resources. Leaders are prepared to work across borders, but persistent barriers remain fragmented regulation, limited data sharing, and uneven access to innovative treatments. To address these urgent issues, we recommend establishing a cross-border task force to harmonize regulatory processes, facilitate secure data sharing, and build consensus among stakeholders—measures that would streamline innovation and ensure equitable patient access to advances in cancer care. We urge all stakeholders to commit to this agenda.

The conference also explored strategies to structure translational cancer research to increase its effectiveness, innovation and reduce global inequalities. Despite major advances in cancer biology that have reduced mortality in high-income countries, significant disparities persist across and within countries, driven by disparities in care, as well as systemic and socioeconomic barriers, and the fact that around 50% of most patients still die from their disease. The conference emphasized the need for a fully integrated research continuum—linking basic science, clinical research to application, and real-world outcomes—to make more scientific progress and ensure all patients´ benefit from this progress. Key priorities include expanding Predictive, Preventive, Personalized, and Participatory Cancer Comprehensive Cancer Centers (CCCs); addressing personal data-driven health, digital health and AI opportunities while continuing to strongly support more traditional areas of cancer research; and embedding HRQoL, outcomes, health economics research and implementation science. A shift toward publicly funded, mission-driven research was strongly recommended to counterbalance commercial dominance, align cancer innovation with quality improvement, equity goals, and because prevention and screening research does not usually attract commercial support. The importance of international collaboration, data interoperability, early detection/intervention and culturally tailored care was underscored, with a strong emphasis on data interoperability to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of cancer research. By investing in prevention, early detection and interception, quality of life, and equitable access, the global cancer research agenda can become a model of solidarity, sustainability, and ethical responsibility.

As Europe faces a rising cancer burden, it is vital to keep cancer research at the forefront of policy. FP10 discussions will begin in January 2026, and Manuel Heitor, former Portuguese Minister for Science, Technology, and Higher Education, has already invited Ulrik Ringborg and me to help prepare a policy article titled “Revisiting Mission-Oriented Cancer Research to Tackle the Increasing Burden of Cancer in Europe: A Policy Perspective.” The article, accepted in Molecular Oncology, aims to ensure that cancer research remains a top priority in FP10. We analyse key challenges and propose policy strategies. We call on all stakeholders—researchers, policymakers, funders, and patient advocates—to actively support and promote our recommendations. We encourage cross-sector collaboration to ensure cancer research remains central in Europe’s agenda.

Reaching where we stand today required building communities, identifying leaders, engaging all the relevant stakeholders along the cancer continuum, organizing science, encouraging collaboration between researchers across borders and beyond, promoting interaction and synergies at EU, national, and regional levels, providing evidence-based advice to inform policy, and speaking with a single voice on wider policy issues.

REFERENCES

1. Jungbluth S, Kelm O, van de Loo J-W, Manousakis E, Vidal M, Hallen, et al. Europe combating cancer: the European Union’s commitment to cancer research in the sixth framework Programme. Mol Oncol. 2006; 1: 14–18.

2. Celis JE & Ringborg U. From the creation of the European research area in 2000 to a Mission on cancer in Europe in 2021-lessons learned and implications. Mol Oncol. 2024; 18(4): 785-792.

3. Ringborg U. The Stockholm declaration. Mol Oncol. 2008; 2: 10–11.

4. Brown H. Turning the Stockholm declaration into reality: creating a world-class infrastructure for cancer research in Europe. Mol Oncol. 2009; 3(1): 5–8.